Martin O’Malley gets his opening, at last

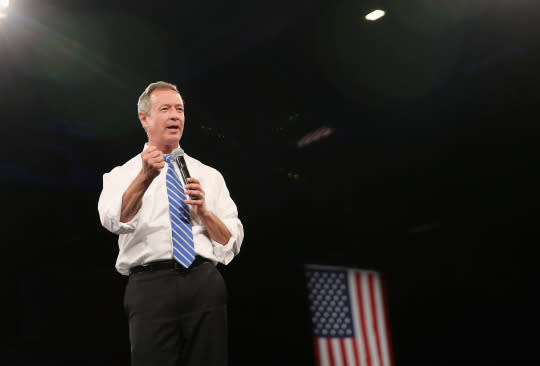

Martin O'Malley speaks at the Jefferson-Jackson Dinner in Iowa in October. (Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

In a little more than a week, Democrats will arrive in Iowa for their second presidential debate. Hillary Clinton will try to solidify her standing as the inevitable nominee. Bernie Sanders will be out to reverse a perceptible slide in the polls.

But the candidate onstage with the most at stake will be Martin O’Malley, the party’s forgotten man.

After toiling away in obscurity for much of the year, barely registering in polls or even in the public consciousness, O’Malley suddenly finds himself — as he likes to put it with his dry wit — in sole possession of third place. “I really feel like the campaign started in earnest 10 days ago, after the first debate,” he said several times, hopefully, as we traveled through New Hampshire this week.

And it does seem to me that O’Malley’s long-awaited opening has finally arrived — if only he can figure out what to do with it.

If Donald Trump has been the year’s most surprising candidate, and Jeb Bush the most disappointing, then O’Malley has been the most enigmatic. A closely watched star in the party as mayor of Baltimore and two-term governor of Maryland, as well as the national spokesman for Democratic governors, O’Malley entered the race as the only executive in the field (excluding Lincoln Chafee, who had only recently switched parties). At 52, he also offered a sharp generational contrast with Clinton and Sanders.

On paper, if you look at the modern history of our presidential campaigns, this should have gotten him a serious look, at least. Sure, most voters wouldn’t have known O’Malley from, say, his friend Luka Bloom, the Irish folksinger. But “new and unknown” isn’t exactly a deal breaker in this environment.

It didn’t unfold that way for O’Malley. He hadn’t even made his official announcement yet when Baltimore blew up in a conflagration of race and violence, leading some liberal activists to denounce his celebrated record as a crime-fighting mayor.

Then Trump and Sanders emerged to dominate the summer’s campaign coverage, leaving little space for anyone else. And that led into the whole Joe Biden drama, which focused a lot of dissatisfied Democrats, throughout the early fall, on an alternative candidate who never emerged.

And while Democrats in 2008 had held nine debates by this time in the race, giving lesser-known candidates plenty of chance to introduce themselves, the party and its autocratic chairwoman, Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, didn’t allow one this year until October — a decision O’Malley acidly protested, to no avail.

All that said, though, it isn’t just external factors that have relegated O’Malley to near irrelevance. Great candidates find a voice that resonates in the moment. For the most part, he hasn’t been great.

There’s a clear market in the party for someone who feels more authentic than Clinton — her partisans will roll their eyes at that word, but it is what it is — and yet more mainstream and electable than Sanders. The problem for O’Malley is that too often he has seemed to be neither.

Hillary Clinton and Martin O'Malley at a Democratic presidential debate in October. (Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Early on, he broke from his more pragmatic political identity to make a populist appeal to the party’s leftmost flank — trying, in effect, to out-Bernie Bernie. O’Malley had a solidly liberal record as governor (he was among the first governors to legalize gay marriage and outlaw the death penalty, and he managed to raise the minimum wage and pass new gun restrictions), but like Barack Obama, he doesn’t make for a terribly convincing populist, even when he mouths the rhetoric of class warfare. “Feel the Mart” just doesn’t work.

And while O’Malley is one of the more sincere candidates you will meet in relaxed settings, that sense of comfort doesn’t always translate to larger rooms, where he sometimes speaks with forced intensity and with an odd, almost retro formality. “We are standing on the threshold of another great American century — of that I have no doubt” is the kind of thing that rolls off his tongue, making him sound like he’s running for mayor of Atlantic City in an episode of “Boardwalk Empire.”

Slideshow: The rise of Martin O'Malley >>>

But if O’Malley hasn’t exactly forced his way into the moment, the moment may finally have come to him. Within days of the first debate three weeks ago, Biden removed himself from consideration, and the two other second-tier candidates who had shared the stage — Chafee and Jim Webb — withdrew as well.

Just like that, the field had winnowed itself to only three candidates, with three months to go before the voting begins.

Then O’Malley gave a fiery, well-received speech at the Jefferson-Jackson Dinner in Iowa, a kind of opening day for caucus season. A poll conducted afterward showed him ticking up from almost nowhere to 7 percent in the state.

O’Malley, a onetime field organizer for Gary Hart in Iowa, has quietly assembled solid organizations in the first two states, managing to rack up dozens of endorsements from local officials who have little to gain by backing him.

His crowds are modest, but they’re also open-minded. “The phrases I hear people repeat to me all the time when I give that talk on a chair across, now, 46 counties in Iowa,” O’Malley told me, “are things like ‘I have never heard of you before. I’m glad I came out. I thought we only had one alternative. I’m glad to know we have a choice. I’m going to learn more about you.’”

And now, as Sanders struggles to keep his momentum, O’Malley will finally get some speaking time on the national stage, too. He was elated this week to see that MSNBC was promoting a pre-debate candidates’ forum, which airs Friday, with a graphic that included his name and face. Progress comes in small victories.

As we drove around this week, O’Malley made clear that he intends to be more pointed in this next debate than he was in the first one, which was mostly an exercise in introducing himself. His strategy is to gain strength through a kind of process of elimination.

Clinton, he implies, is too partisan and too politically malleable to win a general election, and Sanders is too ideologically extreme.

“How can you pull people together when you declare up front that all Republicans are your enemies?” he asked me, referring to Clinton’s striking comment in the first debate. “Or when you hem and haw about whether or not you believe in capitalism?

“I don’t believe that all Republicans are my enemy. They’re my neighbors. And I actually do believe in capitalism when it’s practiced in ways that encourage and defend fair competition and push back against the concentration of monopoly power as the big banks now enjoy it.”

My guess is that O’Malley is right when he says the Democratic race has entered a different phase and remains unsettled. The question is whether he can convert the opportunity.

Insurgent candidates, if they don’t have the kind of compelling personal narrative that an Obama or a Marco Rubio brings to the table, generally have to find that one issue that resonates emotionally with voters, along with a memorable way to talk about it. Think about Howard Dean with the Iraq war in 2004, or Trump with immigration.

During his Baltimore mayoral race in 1999, Martin O'Malley addresses a rally held in response to a police shooting. (Photo: Roberto Borea/AP)

When O’Malley first ran a long-shot campaign for mayor in 1999, as a little-known white candidate in a majority black city, his galvanizing issue was drug crime and how to get it under control. As a presidential candidate, though, he’s had a harder time channeling the emotion of the moment into a singular, persuasive appeal.

O’Malley has talked a lot about inequality and gun control and a rigged political system. He told me, using a basketball term, that he sees himself as the “glue guy,” by which he meant that he’s the only candidate in the race who can build some national consensus around all of these things.

It’s an argument worth making, but probably not the kind that brings a debate audience to its feet. Time and persistence have combined to put O’Malley center stage, but he’ll need something more if he wants to stay there.